|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Port Wars in the Horn of Africa

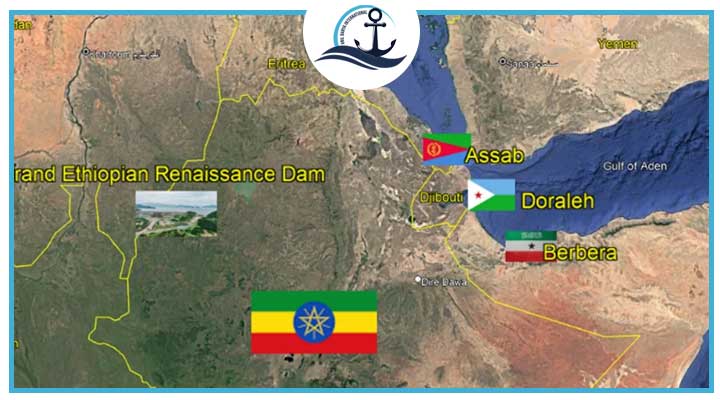

Geopolitical competition around port infrastructure in the Horn of Africa is escalating, as Egypt moves to deepen its involvement in key Red Sea and Gulf of Aden gateways in a bid to strengthen its regional leverage—particularly amid long-running tensions with Ethiopia over Nile water security.

According to Egyptian government sources cited by the UAE’s National newspaper, Cairo is planning to support the development of Assab port in Eritrea and Doraleh port in Djibouti. The initiative is partly aimed at improving facilities for Egyptian naval vessels already calling at these ports, while also serving broader strategic objectives linked to Egypt’s dispute with Ethiopia.

Ports, Power, and the Nile Dispute

Egypt’s port diplomacy comes against the backdrop of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which was officially completed and filled to its design height in September. Cairo has long argued that the dam could threaten downstream Nile flows, placing pressure on Egypt’s agriculture and drinking water supply.

Ethiopia, however, has rejected binding international treaties over water management, insisting on its sovereign rights while pledging responsible operation. In practice, Addis Ababa has controlled Nile flows for nearly five years during the dam’s construction and filling phases—without reducing volumes reaching Sudan and Egypt.

During periods of heavy rainfall in 2022 and above-average rains in 2024, Ethiopia’s management of the reservoir reportedly helped mitigate severe flooding downstream, including in parts of southern Egypt. The dam’s storage capacity also offers a buffer during drought conditions.

Energy, Trade, and Regional Economics

Beyond water security, GERD has reshaped regional energy dynamics. Ethiopia is now generating surplus hydroelectric power—well beyond domestic needs—with capacity projected to reach 13,000 MW by 2028. This cheap electricity is expected to support industrial growth in neighbouring countries once political stability improves, particularly in Sudan.

The energy surplus is already powering Ethiopia’s first internationally developed gold mine at Tulu Kapi, operated by Kefi, which is scheduled to enter production this month.

Djibouti, Somaliland, and Sea Freight Routes

Despite Egypt’s growing interest in Assab and Doraleh, Ethiopia’s external trade remains overwhelmingly dependent on Djibouti, where port infrastructure is operated by China Merchants, following DP World’s removal in 2018. Djibouti continues to function as Ethiopia’s primary maritime outlet for sea freight, containerised cargo, and bulk trade.

As a strategic hedge, Ethiopia last year signed an agreement to lease coastline and port facilities in Berbera, located in the self-declared Republic of Somaliland. The move reflects Addis Ababa’s determination to diversify access to maritime trade routes amid an increasingly contested regional environment.

Limits of Port Pressure

Analysts suggest Egypt’s backing of port development in Eritrea and Djibouti is unlikely to significantly alter Ethiopia’s position on the Nile issue. Governments in both countries have historically separated geopolitics from commercial port operations, prioritising revenue from shipping, logistics, and regional trade.

Some observers argue Cairo could achieve more through diplomacy than confrontation. A further escalation, they warn, might even prompt Ethiopia to exploit regional instability to pursue renewed access to the sea—lost when Eritrea gained independence in 1993.

As competition for influence over ports, shipping lanes, and sea freight corridors intensifies, the Horn of Africa is fast becoming one of the world’s most strategically sensitive maritime regions.